From Flemish books to Scandinavian manuscript fragments

Synnøve Midtbø Myking writes about her research project on medieval fragments

To study medieval manuscripts is also, in many ways, to study the people connected to those manuscripts: authors, scribes, owners, readers. Similarly, to study the movements of texts and books is to study the patterns of human communication, whether these are linked to trade, religion, political alliances, or all of these at once. In my three-year postdoctoral project, Flanders, Norway, and Denmark: Relations and Intertextual Exchanges in the High Middle Ages (funded by the Research Council of Norway), I investigate the connections between medieval Flanders and the kingdoms of Norway and Denmark, and the impact of these connections on manuscript culture in the period ca. 1100–1380. During this time, several important processes took place: the expansion of trade in Northern Europe, the emergence of several new monastic orders, the rise of the universities – and, more locally, the development of ecclesiastical infrastructure in Scandinavia and the full integration of the region into European Latinity.

All of these phenomena contributed towards increased travel between Scandinavia and the continent. Travellers would usually disembark on the coast of Flanders or Northern France before continuing overland. At the same time, Bruges became an important commercial and financial centre, visited by Scandinavians in its own right. A Cistercian abbey near Bruges, Ter Doest, seems to have been especially popular as a stopover for travellers; we have the names of several Norwegians, Danes, and Swedes who visited the abbey over the course of the thirteenth century. At least two Scandinavian churchmen, Peter of Roskilde (d. 1225) and Torfinn of Hamar (d. 1285), are buried there. Incidentally, Ter Doest was also the owner of one of the only two surviving manuscripts containing “the oldest history of Denmark” – Ælnoth’s account of the murder of King Knud in Odense in 1086. The other manuscript belonged to the abbey of Clairmarais near Saint-Omer in today’s France, a town which similarly seems to have had Scandinavian relations. In what way did such relations influence manuscript culture in medieval Norway and Denmark?

To answer that question, we must first attempt to puzzle together the evidence – literally as well as figuratively. Few medieval manuscripts of Danish and Norwegian provenance survive intact, especially those written in Latin. After the Protestant Reformation of 1536/1537, books were collected on a large scale and dismembered, their parchment reused for other purposes, often as binding material on tax accounts and similar documents. As Norway was under Danish rule at this point, it is not surprising that we sometimes find fragments from the same manuscript scattered between the two countries’ collections: a Danish nobleman receiving a fief in Norway might have brought old parchment from a dismembered book with him for binding purposes. Conversely, parchment from a book originally dismembered in Norway might be reused in Denmark. The manuscripts’ medieval provenance can often, but not always, be deduced based on various criteria, such as the size of the original manuscript: in Denmark, it was less common to dismember small-format books for binding purposes. This tendency may be rooted in the fact that medieval Denmark was a richer country and therefore had a larger supply of folio manuscripts that could be reused.

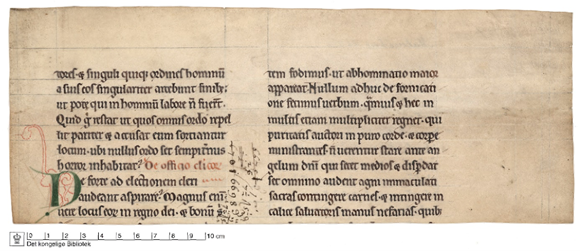

As both Danes and Norwegians had reason to travel to Flanders and the continent during our period, Flemish or Northern French manuscripts could (and did) end up as reused parchment in both countries. One case where it is fairly safe to assume the book was used in Denmark, despite the majority of its surviving fragments surviving in the Norwegian National Archives in Oslo, is a legendary copied towards the end of the twelfth century. In addition to the fifteen fragments in Oslo, two other fragments from this manuscript have been identified so far: a large bifolium in Lund University Library in Scania, and a small strip in the Danish National Archives in Copenhagen. Additionally, fragments from a book copied by the same scribe – a copy of Declamationes de colloquio Simonis cum Iesu by Geoffrey of Auxerre – have been identified in the Royal Library of Copenhagen.

In an article published in 2018, I explored the possibility that the manuscript was a Danish copy of the Legendarium Flandrense, a legendary collection that circulated particularly amongst Cistercian houses in medieval Flanders. The two manuscripts transmitting Ælnoth’s “history of Denmark” belong to this collection, a fact which constitutes a link between Denmark and Flanders. The many characteristically Flemish saints in the fragmentary legendary, such as Aldegunde of Maubeuge and Humbert of Maroilles, point to the same kind of link. Given the secondary provenance of the Geoffrey fragments and the small strip from the legendary in the Danish National Archives, which were all used to bind accounts from Scania – a Swedish region that was part of Denmark in the Middle Ages – it is possible that the books were used in the Cistercian abbey of Herrevad in the vicinity of Lund, and maybe written there. Herrevad owned a copy of Ælnoth’s chronicle – the only one known to have existed in Denmark – which was lost in a fire in 1728, and it is not impossible that this lost manuscript formed part of the Legendarium Flandrense.

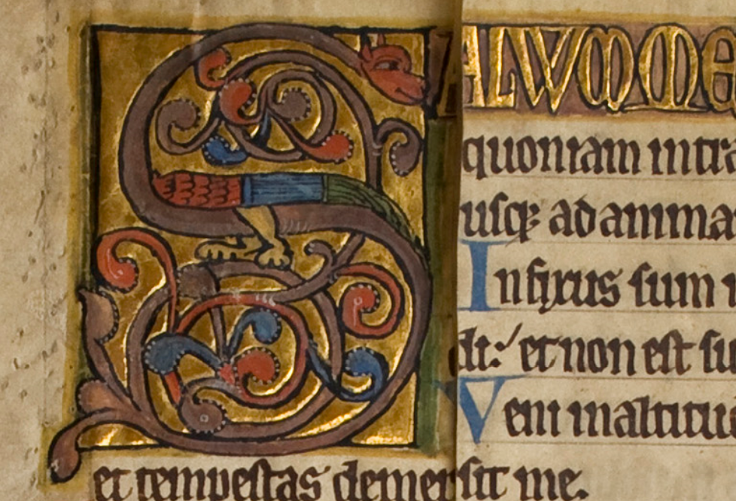

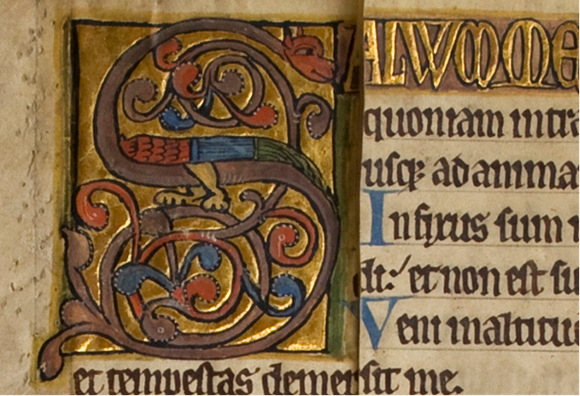

The presence of Flemish or Northern French saints in Scandinavian fragments is one of the most concrete indications of the impact of contact – political, religious, or commercial – on manuscript culture, but often the influence is more subtle, taking the shape of palaeographical or artistic habits. The origin of a fragmentary psalter copied around the same date as the legendary, ca. 1200, was debated until Patricia Stirnemann, an expert on French manuscripts, localised it as Flemish due to the traits of the initial S in Psalm 68, Salvum me fac. The vast majority of the surviving fragments are kept in the Norwegian National Archives, and it is likely that the psalter was used in Norway in medieval times – although recently a small fragment of the same manuscript has been identified in the Royal Library in Copenhagen (I have written more about this psalter here https://flandria.hypotheses.org/29).

The various kinds of impulses – textual, scribal, or religious – which had an impact on medieval manuscript culture are intrinsically linked to the people transmitting those same impulses. Uncovering the networks of ecclesiastics, merchants, and aristocrats that linked the regions of Flanders, Norway, and Denmark together is therefore a central part of determining how books and manuscripts moved between these regions in the High Middle Ages. Such networks explain not only how a variety of manuscripts, from large collections of saints’ lives to small psalters, could make the journey from the Flemish coast to book collections in the North, but also why the owners might bother to take them along for the ride: as souvenirs, objects simultaneously useful and symbolic of status and connections on the continent.