York, Cambridge, crime and punishment

Blog post by CML postdoc Martin Borysek

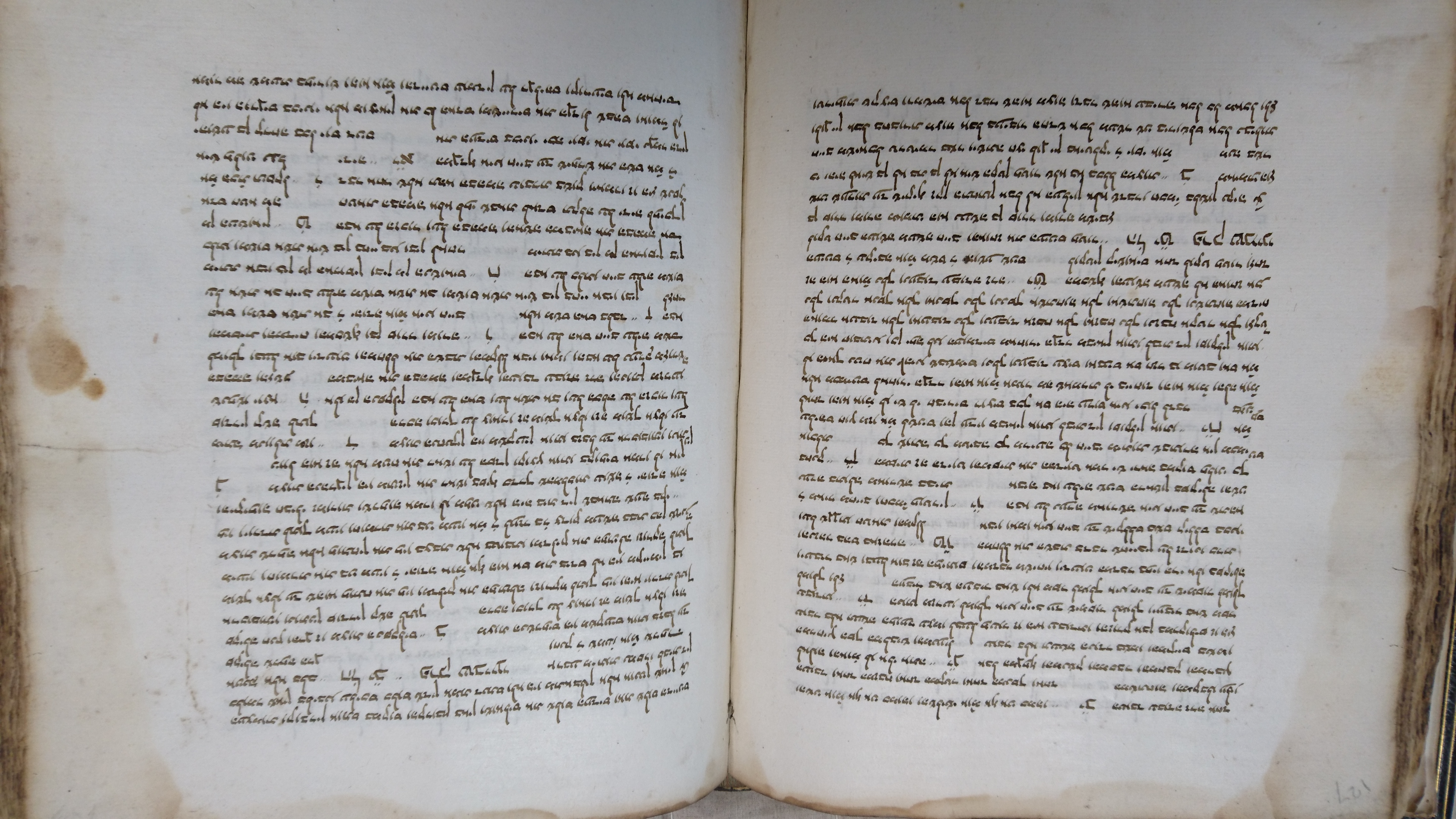

Image: the Cambridge Mishnah, section Sanhedrin, fol. 127—8 .

As my time with the CML draws to its close, I found myself relocated to York full time, saying farewell to Cambridge, my home for the previous eight years.

In the early week of this years, I finally parted with the manuscript of my prepared book, which is now in the trusty hands of the Mohr Siebeck publishers, waiting for their verdict.

In the meantime, I started in earnest preparing my article for the International Medieval review as well as my second book project in which I hope to bring to fruition my research plans which I have been concocting since last spring, namely a study of the more theoretical aspects of the legal status of the Jews in late Middle Ages and the earlier stages of the early modern period, an epoch which may be called (instructively if slightly imprecisely) as the pre-Emancipation Judaism.

One of the defining aspects of the institutional life within the Jewish communities of pre-modern Europe was the specific nature of their legal autonomy, which was generally very limited, but at least in theory guaranteed. Whereas the direct subjection of the Jews to the sovereigns of their respective countries, practised throughout Europe, meant that the Jewish communities were responsible for the management of their inner affairs and thus also for he law enforcement within their own boundaries, the ways and means the Jewish communal leaders could use in doing so were severely limited. Particularly in the area of criminal justice there was not much the Jewish elders could do to make their coreligionists obey the rules, other than shaming them into behaving themselves and threatening to release the transgressors to the secular justice. The actual pronouncement and execution of punishments, however, was by and large in the hands of the non-Jewish authorities.

And yet, the study of the Biblical and Talmudic foundations of the Jewish law’s stance on the matters of crime and punishment remained a core part of the Jewish religious jurisprudence throughout the Middle Ages. Mainly, it was so because it was necessary to know if and to what extent the religious law allowed Jewish communities make compromises with the secular powers.

One of the earliest treatises on criminal justice in Jewish legal literature after the Bible itself is found in the Mishnah, the first major systematic treatise on the fine aspects of the halakhic (ritual and generally religious) law. The Mishnah, compiled by generations of religious scholars in the Holy Land with the final text established by the second century AD, constitutes the older layer of the Talmud (alongside the younger Gemarah) and is one of the most authoritative sources of the Jewish law.

Only three complete manuscripts of the Mishnah written before the advent of the print are known to exist today and one of them, written in the former half of the 15th century in Byzantium with its current binding done some time later in Morocco, is now held in the University Library in Cambridge (as MS Add.470.1).

Therefore, wanting to check the exact text the Jews of the Mediterranean diaspora may have had at their disposal when consulting the Law’s stance on the, I found myself heading back to Cambridge to spend some highly enjoyable time studying, among other things, the Mishnah’s elaboration of the modes of capital punishment practiced during the existence of the ancient Jewish state and under which circumstances it was permissible to condemn someone to day. In a way, nothing could seem more alien to Jews of the late Medieval Europe than the notion that a Jewish entity may have the power of life and death over a human being, but the fact that such matters were still studied and hotly debated in the fifteenth century shows the deep sense of continuity cultivated by the European Jewish intellectuals.