Why ancient and medieval texts are intangible cultural heritage

Lars Boje Mortensen writes about ancient and medieval texts as cultural heritage

Ancient artifacts, art, monuments and ruins are obvious tangible heritage, ideally well taken care of by museums, tourist sites and other organizations. Archaeologists, art and architectural historians, ethnographers and other professionals curate the world’s tangible heritage: without the experts the objects would be meaningless, neglected, and unavailable to the public and to other professionals, such as historians who depend on accessibility and expert scholarship to bring these objects into the horizon of a specific historical understanding. As opposed to the physical residue of the past, UNESCO defines intangible cultural heritage in these terms: “It [cultural heritage] also includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts.” With this program, UNESCO has had a great impact on the recognition and preservation of the diversity of global cultural heritage. The continuous stream of applications to UNESCO for acknowledgement of local traditions testifies to the prestige and success of this program – a standing which is enhanced by the increasing globalisation of all sorts of cultural phenomena.

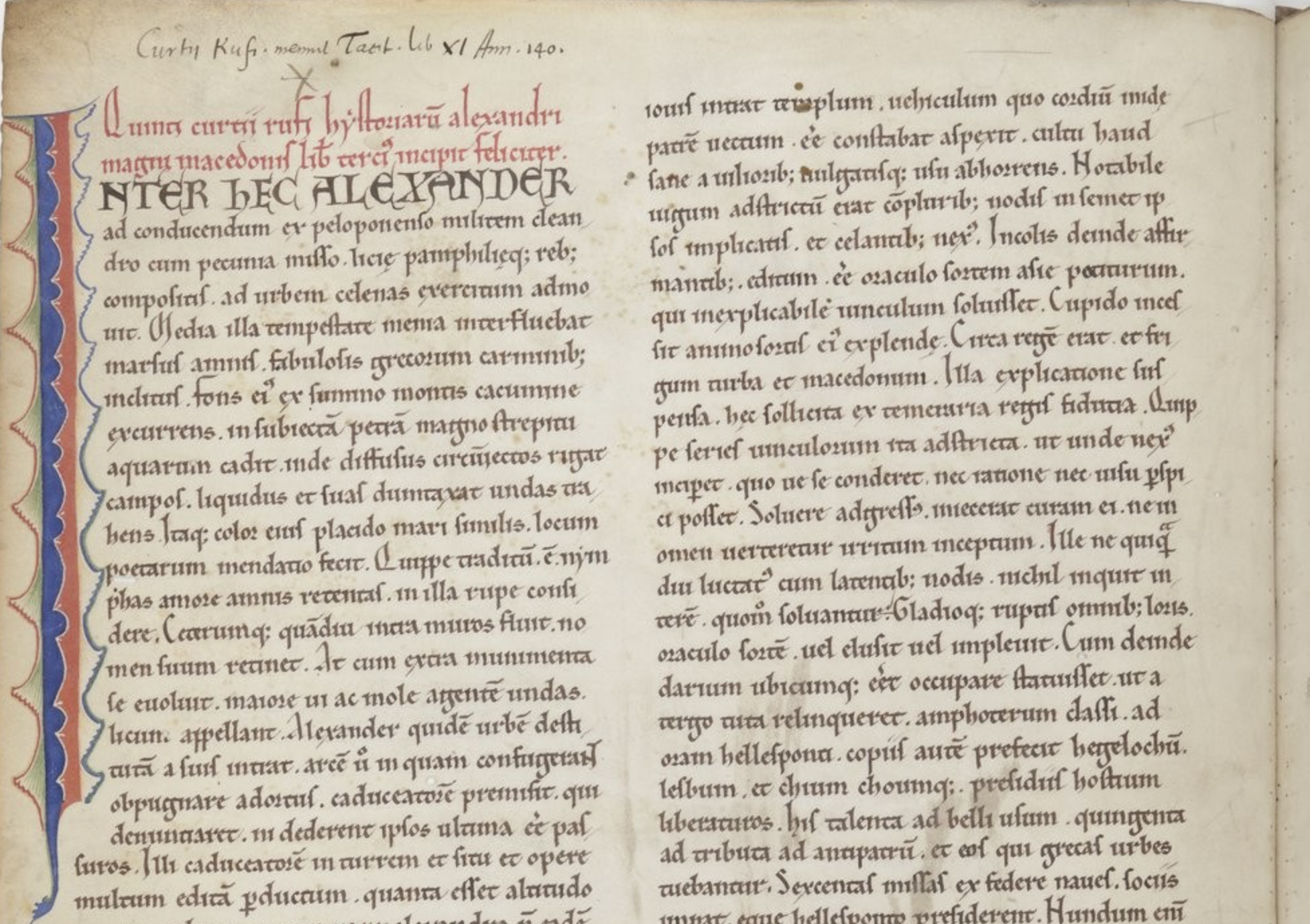

As a textual scholar concerned with exploring and curating ancient and medieval writings, I have often felt frustrated that our activity is apparently left entirely out of the global heritage equation. Such a state of affairs renders vast fields of scholarship and cultural transfer – to the modern world – curiously disarmed in claims for recognition. One reason for this might be that texts can be said to live a life at a somewhat indeterminate point between the material and the abstract realms. All written texts obviously exist in a medium, and in the last three decades or so great research has been conducted exactly on the significance of textual carriers in both their communicative and technological context – a trend referred to as a “material turn” or “new philology” within the relevant fields. But there was a reason that the material context had been underplayed, namely because it is possible to deal with texts in an abstract manner. There is both a real and an ideal core of textual identity between a medieval copy and a modern edition, translation, reading, performance etc. So while a precious medieval manuscript can form part of the tangible UNESCO heritage, the text it helps to transmit is so much more than that and should – I would argue – count as intangible heritage because it actually does not exist without its modern practitioners, curators and … readers.

Another reason that ancient and medieval texts have fallen by the wayside in heritage discourse is perhaps the argument that they are doing very well on their own. The great ancient books of religion and wisdom form the most obvious example, enjoying a rich and diversified life in all kinds of modern reproductions, languages, liturgical practices, theological disputes, websites and so on – and command an enormous global constituency. Something similar – although on a smaller scale – could be said about the great classics: Gilgamesh, Homer, Plato, Sima Qian, Vergil, Augustine, Ibn-Sina, Firdouwsi, Maimonides, Ibn-Arabi, Mahabharata, Dante, Chaucer, etc. all have academic societies, fan clubs, websites and, like the major religious texts, a firm place in various curricula. The idea of intangible heritage was probably formed as a contrast to this extremely strong, and often imperialistic set of dominant and secure texts.

But these are the canonical tip of the iceberg. What about the 99% of extant texts beneath and beside them? I am referring to the cornucopia of less-known religious paratexts, literary, historical and philosophical writings which are not only needed for understanding and contextualising the canonical works, but, more importantly, provide extremely precious – if fragmentary – access to any historical approach to pre-modern societies in their ‘objective’ structures as well as their ‘subjective’ viewpoints and aesthetics. Many such texts are being curated by specialised scholars across the globe, mainly organised along national, linguistic or confessional lines. This obviously implies a certain local bias reflecting genuine local interest, but it also creates some serious blind spots (a straightforward example is the written record of the extinct world religion of Manichaeism which spanned most of Eurasia until the Middle Ages and today is the remit of very few specialists). While there will never be a neutral Archimedean vantage point from which to study ancient and medieval texts – that would be a sad cold death for this extensive human output – I would argue that both the canonical and the less canonical texts would in the long term benefit from a more global framing and curating than is the case at the moment. All of these priceless textual survivals from a world long gone belong to us all – not only to the dedicated religious, language-defined or national communities. A recognition of their special status as both global tangible heritage (the surviving inscriptions and manuscripts) and intangible heritage (the texts migrating through media) would help us see this bigger picture. A reconceptualization of both sides of this heritage would play into debates on digitization – with all the valuable work being done by libraries, archives and non-profit organizations – and into the wider question of how to curate the growing digitized archive in dialogue with research and teaching practices.

So what makes the ancient and medieval textual record special? Why does it deserve a special status in terms of global curating? I think three main reasons can be adduced: (1) the specific textual fluidity before printing, (2) our distance to the relevant main languages, (3) the disproportionate weight of the textual record in understanding the distant past.

(1) In ancient and medieval book and written culture, every copy of a text was unique. This meant that the conditions of authorship and textual identification were radically different than in the culture of printing (in China with emerging efficiency from the 12th century, in Europe from c. 1450 with sudden change and global impact). The boundaries between copy, paraphrase, abbreviation, excerpt, and reference were fluid (although the most canonical texts resisted them with a lot of effort and some success); equally fluid were the differences between author, editor, commentator, translator and copyist; and publication of a text was not a unique, identifiable moment (as with print), but a series of painstaking and expensive dissemination moments, often over a very long time. Furthermore, the continuous reworking of verbal art and narrative and intellectual content in the copying process increasingly tended to anonymize writing (again except for a few canonical authors who would, in a countermove, attract anonymous texts to their names). All this means that the global archive of ancient and (most) medieval texts was not accumulative in the same simple way as that of printed texts, and that their modern rendition into new media requires a whole set of extra explanations and manoeuvres of textual disentanglement; it also implies continuous negotiation between the inherent restrictions of manuscript (and epigraphic) technology and the constantly emerging modern storage and retrieval systems. The nuts and bolts of manuscript technology makes the job of curating old texts an incessant back and forth between the tangible manuscripts, specific philological traditions, and the intangible text – which is therefore a more delicate, but in a sense also more abstract, object than those of the printing age. There is never a secure, identifiable watershed mark like the folio edition of Shakespeare.

(2) Our distance from the main ancient and medieval written languages is of a sort that alienates us from the originals in a qualitatively different way than from, say, the 16th- and 17th-century texts which can often be mastered with just a little training in the relevant modern educated version of the same language. It can be claimed that some high or late medieval written languages are fairly close to the modern standard, but this is often more of a modern national wishful dream, and it certainly does not hold true of the dominant linguistic vehicles of ancient and medieval texts: the imperial languages of Sumerian, Akkadian, Greek, classical Chinese, Latin, Arabic, and the cosmopolitan languages of Aramaic, Sanskrit, Church Slavonic, Persian and Hebrew account for the lion’s share of the relevant textual record. Training in some of these ancient languages are still thriving in religious and national educational systems, but for others the situation is more precarious; in any case a global view of securing the competences necessary for curating in the longer term still seems to be missing, as does the recognition that all these languages enshrine a wealth of global heritage texts.

(3) The last point regards the role that the ensemble of ancient and medieval texts play in our historical understanding, broadly conceived (including history of religions, literature etc.). My contention here is that our access to the older historical period of Eurasian and north African history, at least before the 13th century, disproportionally hinges on texts. Needless to say, our understanding of modern history can draw on a multimedial mass of resources as well as on our own life experiences, all modern scientific discourses as well as on societal attitudes and structures still in place. Such access is less privileged for the early modern period, but still impressive, including not only a wealth of easily identifiable and datable printed texts but also of images, recognizable town- and landscapes, languages, intellectual discourses, music and more. A few of these elements may even seem familiar for what we call the late Middle Ages (or early Renaissance) in Europe, but when we pass beyond the threshold of c. 1200 – before the significant 13th-century expansion of the written record throughout Eurasia and northern Africa – our sources of knowledge and of historical imagination are dramatically reduced: except for some ancient statues in Mediterranean Europe, we have no iconic contact to the likenesses of historical actors, the languages are almost all quite distant, the music is virtually unknown, authentic town- and landscapes can rarely be glimpsed, most surviving buildings are only ruins. We have in fact only two points of access: the archaeological / art historical remnants and the textual record. So much relies on those two sets of evidence, and both are worryingly fragmentary. There is very little institutional continuity which would have secured any systematic survival or revival. This in itself makes our curating, evaluating and recontextualising of surviving texts from before printing, and especially before c. 1200, absolutely key to our continued engagement with this distant history. In fact, one could make the argument that a special type of hermeneutics is at play here, because each text, even the non-canonical, carries too heavy a load, forced to fill in all the gaps of the unknown (in the same way as the equally sporadic but crucial archaeological sites and extant pieces of art). This is, coincidentally, also a period in which we may find much that alienates us in terms of humanitarian rights and political ideals, but nonetheless an age which left us a marvellous, if badly fragmented, record of human experience. It is a period, moreover, whose texts can still transmit to us either religious allegiance or fascination, philosophical reflection, narrative excitement, and rhetorical and poetic beauty.

What I argue for here, is not the establishment of any new UNESCO list, nor any special resources for textual curators that they do not already have. I simply want to open up the question of what a global perspective on this heritage would bring to our practices, and to invite reflection on the categories of the dominant heritage discourse which seem to leave the powerful non-material aspect of ancient and medieval texts out of consideration. In the FARO convention, (Council of Europe 2005), one reads the definition “Cultural heritage is a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions. It includes all aspects of the environment resulting from the interaction between people and places through time”, and further on: “heritage community consists of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations.” These definitions are clearly concerned with tangible heritage, but there is nothing in them that precludes the intangible heritage of ancient and medieval texts. What we need to promote are research and teaching practices that can situate the ancient and medieval textual record within a global heritage understanding. The existing faith-based or national curating should increasingly be supplemented with non-confessional and non-nationalising frames which emphasize the historical, intellectual and aesthetic value of this global intangible heritage.