From Acre to Chantilly: Rhetoric, Crusades, and Translation

Julian Yolles writes about his travels to Musée Condé in Chantilly where he examined a manuscript with CML colleague Rosa M. Rodríguez Porto

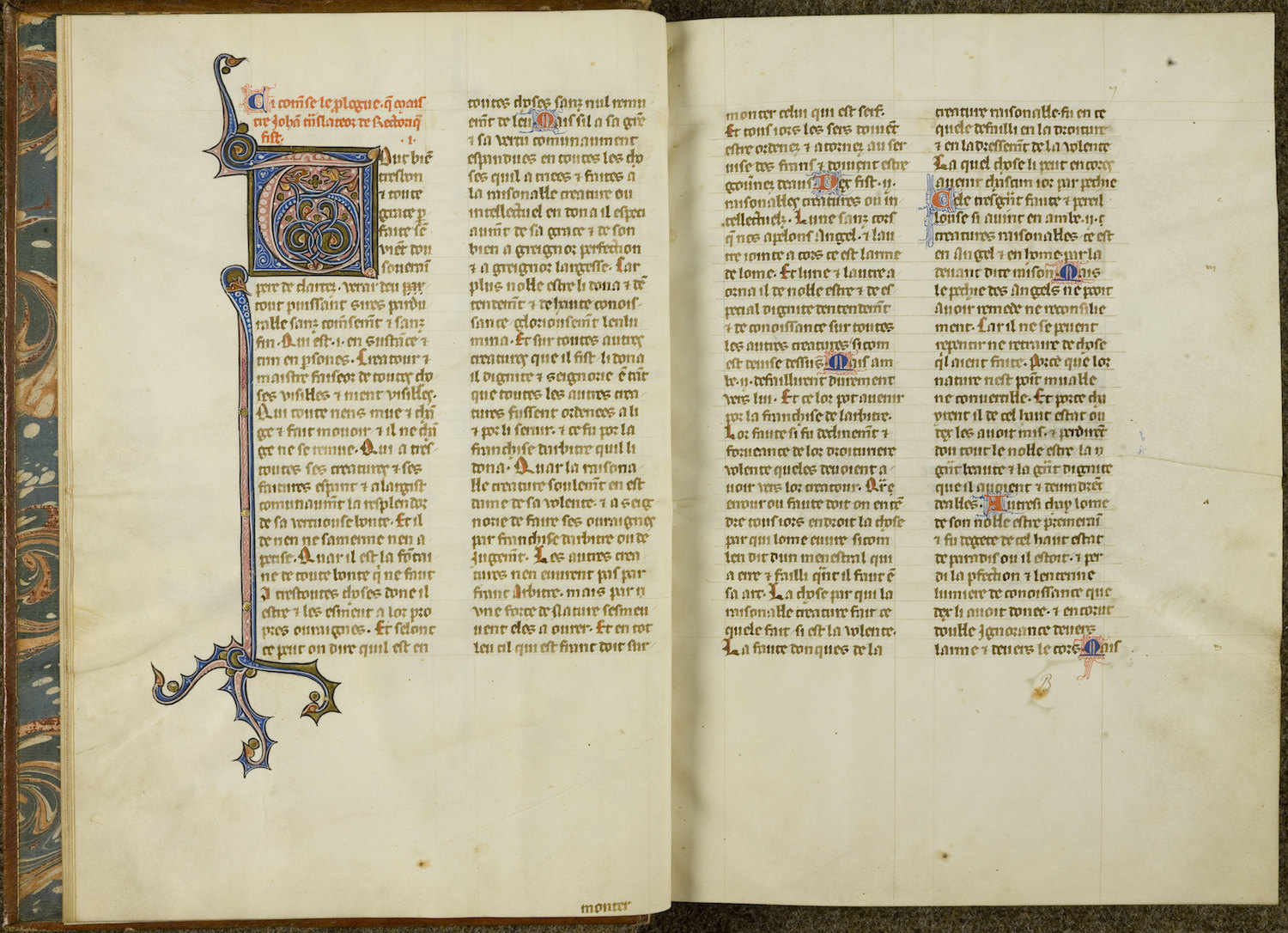

Top image: Chantilly, Musée Condé 433, f. 6v-7r

To most people, the word “crusade” is unlikely to conjure up notions of learning and bookishness.

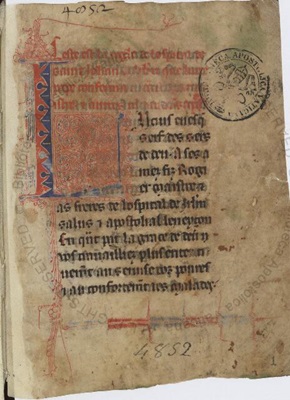

Increasingly, however, we are beginning to acquire a better understanding of some of the remarkable intellectual activity that occurred within a crusading context. Take for example the manuscript known by the shelfmark Chantilly, Musée Condé 433: less than 10 years before the fall of the last crusader stronghold in the Levant (1291), a master of the Knights Hospitaller in the city of Acre commissioned this richly illuminated manuscript containing the first French translation of two ancient rhetorical treatises (Cicero’s De inventione and the Rhetorica ad Herennium). Intrigued by the ways in which this object brings together such disparate themes as Roman rhetoric, crusades, early French translation methods, and Latin-Greek relations, my colleague Rosa M. Rodríguez Porto and I traveled to the Musée Condé in Chantilly last February to examine this manuscript in preparation for a joint paper at the Medieval French Without Borders conference at Fordham University (now due to be held in 2021).

Situated some 50 km north of Paris, the Musée Condé is housed in the imposing nineteenth-century edifice of the Château de Chantilly (the earlier building was destroyed during the French revolution). It counts among its holdings such renowned treasures as the beautifully illuminated book of hours of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Raphael’s Three Graces, assorted paintings by Fra Angelico and Nicolas Poussin, as well as Piero di Cosimo’s delightfully idiosyncratic portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, depicted as Cleopatra with a snake around her neck.

Among these priceless objects, Musée Condé 433 holds a far less prominent, but by no means undeserved place. Numbering 164 folios, this handsome codex contains within its pages several firsts: the texts copied on them are the first French translations of Cicero’s De inventione and the anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium (here, as so often, attributed to Cicero). Moreover, these works receive here for the first time a cycle of miniatures, illustrating, for instance, Cicero’s passage on the civilizing force of rhetoric (as shown in two panels depicting city ramparts being torn down and reconstructed again) and his anecdote of the painter Zeuxis of Heraclea (seen in the process of painting a composite portrait of the maidens of Croton).

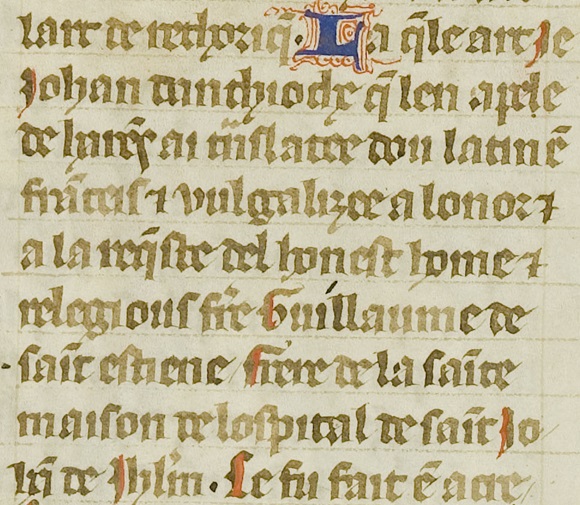

Fortunately, we know the identities of both the translator and the patron who commissioned this manuscript, and while the artist’s name remains a mystery, his designs produced in both Paris and Acre (including illuminations for French bibles and for French translations of the chronicle of William of Tyre) have become so well-known as to earn him the moniker of the “Paris-Acre Master.” From a statement made by the translator in his prologue to the translations, we learn that he was John of Antioch (Johan d’Anthioche) and translated the works in Acre in the year 1282 at the behest of Guillaume de Saint Estiene, brother of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem (the date is actually written here as 1272, but other references in the manuscript indicate that this was an error).

Both John of Antioch and his patron are associated with various other learned activities. John, at several points identified as a “master” (maistre), appended to his rhetorical translations brief treatises on logic (largely deriving from Boethius) and on principles of translation. He also translated into French Gervase of Tilbury’s Otia imperalia, an early thirteenth-century Latin collection of classical and biblical stories originally written for the German emperor Otto IV. Guillaume de Saint Estiene, also known by the anglicized William of St Stephen and the Italian Gullielmo de Santo Stefano (his point of origin remains a subject of scholarly debate), was a well-known Hospitaller master and later commander in Cyprus who also commissioned the translation of the Hospitaller Rule and related documents, and composed an original account of the foundation of the Hospital.

What drove a Hospitaller master in Acre to commission such deluxe translations of Ciceronian rhetoric? No straightforward answer easily presents itself to this obvious yet elusive question, though it is clear that Guillaume de Saint Estiene cultivated an interest in history. Moreover, masters of the military orders were frequently forced to manage legal disputes, and he may have wished to benefit from ancient rhetorical strategies in a more accessible version made available to him in the vernacular—or, given the ostentatious nature of the manuscript, at least to display his command of such knowledge to other masters and nobles.

John of Antioch may have had something to do with the choice of texts as well. His association with the city of Antioch brings him into connection with a more extensive tradition of translation and rhetorical learning that far predated the Latin conquest of the city during the First Crusade in 1098. In recent years, the contours have emerged of an extensive translation movement centered in and around eleventh-century Antioch (especially, but by no means exclusively, from Greek into Arabic). Under the crusader rule of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Antioch carried on its tradition as a hub of translation activity, which now also extended into Latin. For instance, the twelfth-century scholar Stephen the Philosopher translated medical and cosmological works from Arabic into Latin and commissioned two scribes to copy for him the Rhetorica ad Herennium (and, almost certainly, Cicero’s De inventione).

Part of what made Latin Antioch so unique was its large Greek Orthodox community; this, combined with the city’s proximity to the Byzantine sphere of influence, created a complicated and often contentious intellectual, religious, and political dynamic. One miniature in Musée Condé 433 evokes the complex relations between Greeks and Latins in a startling way: accompanying a passage in which Cicero debates Roman indebtedness to Greek intellectual tradition, the painter has transposed this dynamic onto the thirteenth-century Levant by depicting a classroom scene in which pupils are seated between a Latin Christian teacher on the left and two Greek instructors (sporting Palaiologan hats) on the right.

Contrary to traditional assumptions, recent scholars have observed that some of the most groundbreaking developments in early French translation occurred outside of France. The sheer innovation displayed in both the translations and the visual designs of Musée Condé 433 bolster this notion and show how, paradoxically, the challenging environment of the crusader Levant could have been more conducive to intellectual innovation than metropolitan France.

I look forward to examining in greater detail this and other expressions of classical learning in a new project on Classical learning in the Latin East, for which I have recently received a grant from the Humanities Council of the University of Southern Denmark.