Cli-fi teaches us about the future

Climate literature is becoming one of the most prominent genres of the time. It is highlighted for its contributions to the climate debate, because it makes a future with climate change tangible for us. Students at SDU now have the chance to try out the effects of climate fiction in the competition Write the Future.

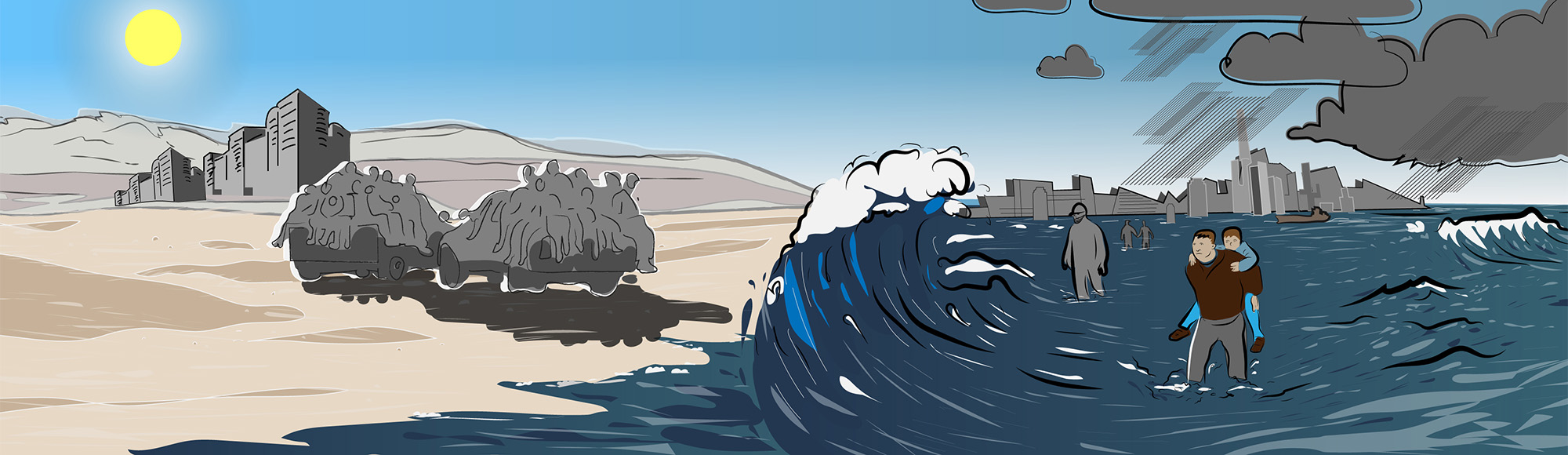

Right now, climate literature is booming. These stories describe a future in which large parts of New York are flooded; Britain has built a metre-high wall that keeps rising water levels and climate refugees out; and climate activists are meticulously keeping track of their CO 2 consumption, using the exercise bike to provide power to the computer and refusing to have children until they are CO2 -neutral.

Many sources in the literary landscape highlight climate literature as an important player in the climate debate.

The reason being that the new genre – cli-fi among experts – can help us imagine a future marked by the climate crisis. And it can prepare us to act now to stop some of the worst consequences of climate change.

”Climate literature makes us better prepared to think about a future with climate change, and that’s important. Because when we can imagine the future, we can actually address the problems.

Literature in the public debate

But can climate literature really teach us about a future with climate change? Both yes and no, says Bryan Yazell, Assistant Professor at the Department for the Study of Culture.

He researches how literature – especially on migration – affects and reflects the public debate. And he has recently studied how climate literature describes the huge challenges of the future with millions of climate refugees.

According to climate literature, what does a future with climate refugees look like?

– It’s very much a gloomy future that climate literature describes. It’s characterised by lots of homeless people moving around in communities characterised by inequality. There is widespread consensus in the descriptions in both sci-fi and cli-fi that the people of the future will live in the streets.

– The imagination in relation to migration problems in the future is quite limited. Literature borrows and recirculates our stereotypes of, for example, migrants and the tensions between North and South. So, rather than predicting the future, climate literature mobilises strong and understandable symbols and ideas from our culture and history that emphasise the need for change.

What can we learn from this?

– Part of the climate literature uses emotionally powerful stereotypes to describe a future when people in Texas or California become climate migrants and, recalling migrants from Latin America today, struggle to climb over the wall to the better opportunities in the North.

– In this way, efforts are made to give readers a better understanding of the situation of climate migrants and perhaps increase sympathy with today’s refugees and migrants who are already on the run from the consequences of the climate crisis.

– By addressing these overwhelming problems, which many people still cannot or will not realise, climate literature makes us better prepared to think about a future with climate change, and that’s important. Because when we can imagine the future, we can actually address the problems.

Are there also problems in cli-fi’s reuse of stereotypes?

– The literature’s inclination to stereotypes and the lack of focus on voices and experiences that have in fact already been marginalised by climate change certainly carry a risk. Especially in relation to maintaining the somewhat naive notion of the western affluent countries that we’re going to be fine and not that affected by climate change.

– It may end up overshadowing the seriousness of the situation, so that the huge challenges posed by migration due to climate change will not be dealt with politically.

Does climate literature really make readers act?

– That question needs to be investigated more thoroughly. Preliminary studies suggest that some readers actually change attitudes in relation to climate challenges, and they are more likely to change attitudes when reading climate literature about environments and people that resemble something, they know of themselves.

– When it comes to actions, the changes are quite limited. And if readers act, it’s mostly on the personal level, that is, that they change some of their personal habits.

Bryan Yazell recommends: The 3 best cli-fi novels to read

New York 2140 (2017) by American author Kim Stanley Robinson

A large, genre-bending novel set after rising sea tides flood New York City. Robinson’s text is remarkable not only for presenting a plausible account of life in the next century, but for showing the similarities between the future and the present. In the novel, climate change provides yet another opportunity for wealthy interests to take advantage of the vulnerable and to profit from disaster. New York 2140 is also distinct for offering concrete, achievable policies (which largely resemble the “Green New Deal” in the US) for addressing these problems. Robinson demonstrates how climate fiction need not only focus on destruction but can also outline ideas we can take advantage of today.

Station Eleven (2013) by Canadian author Emily St. John Mandel

Readers may find Mandel’s novel, which is set after an apocalyptic pandemic nearly wipes out the human population, compelling reading while waiting for lockdown to end. Although apocalyptic scenarios are common in recent fiction, Mandel’s novel thoughtfully identifies the consequences that follow in the wake of climate change: not only deadly disease outbreaks but also the disappearance of luxuries we often take for granted, like smartphones and air travel. Taking stock of what is lost, the novel considers what ideas and practices are worth struggling to keep.

Memory of Water [Teemestarin kirja] (2012) by Finnish author Emmi Itäranta

Itäranta depicts a dystopian future where water scarcity has completely remade society in ways large and small. For instance, the novel is set in a region of Europe known as the Scandinavian Union, which is occupied by China. Amid this backdrop, a seventeen-year-old girl takes on the responsibility to find—and protect—water for her village. Like the best of young adult (YA) fiction, the story’s protagonist undergoes a rite of passage that forces her to learn how to apply (and when to abandon) the wisdom of the previous generation. While the dystopian elements recall other examples of YA writing, the novel stands out with and its lyrical style and its depiction of northern Europe changed by climate change.

Meet the researcher

Bryan Yazell is an Assistant Professor at the Department for the Study of Culture and a Fellow at DIAS at SDU. He researches how literature – especially on migration – affects and reflects the public debate. And he has recently studied how climate literature – so far, based in English literature – describes the huge challenges of a future with millions of climate refugees.

Write your future

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered our daily routines: work, leisure and even trips to the local supermarket are different than before. Will things eventually return to normal – or will the pandemic have changed life as we knew it?

One of the many qualities of fiction is that it allows us to "test-live" different lives. We invite all students at SDU to join a literary experiment to envision the future and understand where we might be heading. Write a short story in Danish or English that depicts a typical day in your life in the year 2025 and participate in the competition Write Your Future.